SE101: Smishing Attack Overview and Breakdown

‘Smishing’ is a blended word comprised of "SMS" (short message service)and "phishing." In short, it's a social engineering attack vector that leverages text messages to deceive individuals into taking several actions (outlined later in the post).

Following on from the SE:101 Series created by Chris Pritchard, featuring blogs post by both Chris and I, this is the latest post in the series, which covers ‘Smishing’, a lesser known, but highly prevalent social engineering attack vector.

What exactly is ‘Smishing’?

Common tactics employed in smishing attacks include masquerading as reputable entities, such as banks, government agencies, or well-known service providers, family and friends. These messages often contain links or phone numbers that, when interacted with, can lead to the compromise of personal information or the installation of malware.

Given the prevalence of mobile devices in our daily lives, smishing has become an increasingly favoured tactic among cybercriminals. As such, it is imperative that we remain vigilant and educate ourselves, our colleagues, family and friends on recognizing, and avoiding such deceptive messages to safeguard our sensitive information, or in the case of business, its proprietary and customer information.

So how does ‘Smishing’ work at a high-level?

Well, this is a form/variant of a ‘phishing’ attack, in which an attacker uses a compelling text message to lure, build rapport and ultimately trick the targeted recipient(s) in to the doing any or all of the following:

- Clicking a link which will have malicious intent or consequences

- Sending the social engineer/threat actor private information

- Sending the social engineer/threat actor financial information

- Making a purchase for gift certificates/store cards e.g. Amazon, Apple…

- Downloading malicious programs/software to a smartphone or other hardware devices

It is worth noting that the social engineer/threat actor, or the ‘Smisher’ as we’ll now refer to them, may use your actual name and location to address you directly. Using these details make the pretext of any message more compelling for the recipient.

Lets Breakdown a 'Smishing' Attack

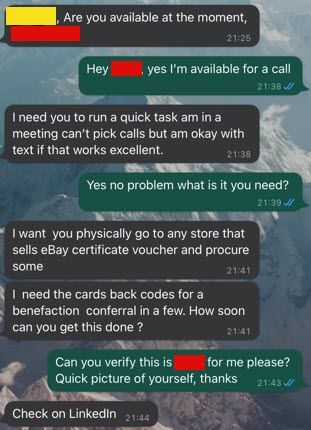

The following breakdown is taken from an actual ‘Smishing’ attack which targeted an individual using the pre-text or ‘lure’ of urgency and a position of authority. I should point out, at this stage, that the smishing attack featured, was ultimately unsuccessful, due to the security awareness of the targeted individual and their ability to challenge politely but firmly.

Using the following image, which depicts the ‘Smishing’ attack message exchange, we can break down the ‘Smishers’ approach/methodology.

Note: the SMS conversation has been redacted to protect the recipient’s identity (yellow box), as well as the senior figure being impersonated (red box).

Step 1) OSINT: The ‘Smisher’ has clear done some open-source intelligence gathering (OSINT) and identified a senior figure of importance within the target organization. (Easily done via LinkedIn, Corporate publications/resources, news articles, media coverage etc.)

Step 2) Identify targets: Using data breaches, social media platforms, sources of public record, a social engineer/threat actor can enumerate an individual or groups of individuals information. Once a target list has been constructed, depending on the technical ability of the ‘Smisher’ or threat actor, both manual (time consuming) and automated (most efficient, as allows for mass campaigns) means can be used to launch the attack.

Step 3) The Pretext: In our example, the ‘Smisher’ poses as a high profile, well known and important individual, within the target organization. This is then supported with the “lure/enticement”, and this is conveyed in the following forms:

- First: A closed question first (e.g. a question that is either a yes/no)

- Second: Politeness

- Third: Needing Help third

- Fourth: Urgency fourth

- Lastly: Directness last (issuing a request, with the initial pretext set as coming from a high profile/important individual)

At this point, Directness, the ‘Smisher’ will either succeed with the lure, get caught out, or attempt to enacted a secondary pretext/lure! In our case they got caught out, as when the colleague issued the verification challenge, requesting a current picture, the ‘Smishing’ replied with “Check on LinkedIn”, at which point, the targeted recipient ceased all further interaction with the ‘Smisher’ and reported the incident to the organization security team.

So, how can we Protect Ourselves from Smishing Attacks?

We all know about email phishing, the dangers of it and what to look for, but ultimately if it feels ‘off’ we call it out! Protecting ourselves from ‘Smishing’ attacks, we need to take the same approach; however, smishing prevention, much like phishing prevent, depends on the targeted user’s ability to identify a smishing attack and ignore or report the message. With this in mind, here are some simple steps, as an individual, to be aware of:

- Check the listed Caller ID; this usually points to an online voice over IP (VOIP) provider, where looking up the number and its location is not normally possible.

- Check the message, grammar, spelling and structure

- Don’t click on any links which you are unsure of the origin or validity

- Don’t send anyone private information via SMS

- Don’t send anyone financial information via SMS

- Don’t make purchases for gift certificates/store cards e.g. Amazon, Apple… if asked to do so via SMS

- Don’t download malicious programs/software to a smartphone or other hardware devices if asked to do so via SMS

- Ultimately be aware of your social media/online presence and what you make available

In addition to the above point, there are several technological solutions which can also prevent, or act as defense in depth:

· SMS Filtering: Many smartphones/cell phone carriers now provide ‘SMS filtering’ options to identify and block or flag suspicious SMS’s.

· Multifactor Authentication (MFA): Utilizing MFA is an additional protective layer, will serve as an additional layer of defense and can prevent a threat actor from using credentials obtained through ‘Smishing’ attack.

Anti-phishing Tools: Some security applications for mobile devices, for example, Google Chrome’s ‘Safe browsing’ and IOS’s ‘Built-in Privacy & Security’ protections, can help identify phishing links in text messages and prevent users from accessing malicious sites.

Closing Points

Anyone with a mobile device, such as a smartphone or tablet, can receive regular cellular text messages, from any number in the world, or indeed via any supported applications e.g., WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal. Many users are already aware of the dangers of clicking a link in email messages; however, fewer people are aware of the dangers of clicking links which are contained within SMS messages and ‘Smishing’ attacks.

In short:

- Ignore: If it looks too good to be true and/or the message is unsolicited, ignore, report and delete. SMS messages offering quick money from winning prizes or collecting cash after entering information.

- Remember: Financial institutions will never send a SMS asking for credentials or a money transfer. Never send credit card numbers, ATM PINs, or banking information to someone via text messages.

- Avoid: avoid responding to a SMS/phone number that you don’t recognize.

- Awareness: Make an effort to stay up to date with current smishing tactics and threats. Awareness can be your first line of defense. As an individual this maybe seem like a daunting task; however, your current organization may have security awareness program which covers topics such as this, as such this would be a great place to seek help and understanding. Alternatively, seeking knowledge online from reputable providers can also be another great option.

As users, we are much more trusting of text messages in this day and age, as this is normally the main means of communications between family and friends, so ‘Smishing’ is often lucrative to attackers seeking to build rapport and obtain credentials, banking information and private data.